Project Context

Teaching staff

were given one hour of general introduction to Firefly in late June 2014.

However, the system was not online until mid July (during summer break). Staff

were given a faculty based refresher in late August 2014, which was the first

time we were given access to view and edit our own pages.

All

staff have been given an appraisal goal of "Having pages on Firefly by

October half term" (October 20-24). If staff have problems with using the

site we are directed to the company helpline: there has been very little

guidance or support from either school management or IT services. This situation

is compounded by having teaching staff who run the gamut of experience, from

those who have run VLEs before (albeit on different platforms) to those who

have difficulty turning on a projector. In my twenty months at the school, the

only IT professional development or training before Firefly’s introduction was a twenty minute brief on using search

engines such as Google. The school runs a mix of Macs and PC based computers

and software and this is also causing problems: there are some minor

differences between the two platforms that have caused some confusion. There is

no whole-school approach: staff have been left to their own devices to figure

out how to teach online, rather than establishing collaboratively decided guidelines for learning and

participation (Palloff and Pratt, 2000).

Power

and Gould-Morven (2011) note that ‘although

administrators typically champion support of OL [online learning] , they often

seem unable or unwilling to marshall the necessary financial, human and

technological resources to produce high-quality course materials and to effect

efficient course delivery’. In this case, the

resource most lacking has

been exactly what management expect to see from Firefly. Referred to by one

staff meeting a “place where students can find what they need”, the follow up

meeting notes read “Firefly Pages: A reminder that all staff need to complete their

Firefly page/s, one of the 2013-14 objectives, by half term. There should be key information/resources uploaded for every

class” (Southbank International School, 2014). Individual staff are being left

with the autonomy to decide on format, but exactly what constitutes key

information/resources has not been clarified.

Personal context

I currently

teach Grades 6 11 music, using the Middle Years Program (MYP) and Diploma

Program (DP) of the International Baccalaureate. A highly regarded curriculum,

it basis its philosophy of teaching and learning in an explicitly inquiry based

approach, focusing on issues such as concept based learning, transference of

learning from one context to another, and a strong emphasis on teaching and

assessing learning skills. The IB is also leading the world in the use of

e-assessment, with the MYP running it's first matriculation e-exams in May 2014

(IBO, 2014a).This is a curriculum that expects students to take responsibility

for their own learning, advocates assessment for learning, and expects that

schools will product global citizens with the intellectual and learning tools

needed for twenty-first century learning and working:

The MYP emphasizes intellectual challenge,

encouraging students to make connections between their studies in traditional

subjects and the real world. It fosters the development of skills for

communication, intercultural understanding and global engagement - essential

qualities for young people who are becoming global leaders (IBO, 2014b)

The MYP

released a new curriculum (MYP: Next Chapter) in March 2014. While northern

hemisphere schools are not expected to be 100% compliant until May 2016, we

have been expected to show strong implementation of the program from the start

of the current school year. This means that not only are Southbank staff using

a new data management system and a brand new VLE, but also designing content

for a brand new curriculum.

My first experience

of VLEs was in Hong Kong as part of a response to schools being closed during

the 2003 SARS outbreak. All schools in the territory were closed two weeks

early for the Easter break in the hopes that this would prevent the spread of

the virus. In a city and region where education is hugely valued, all schools,

whether government, private or international, were under immense pressure from

the government and parents to find ways of continuing teaching, especially

given that no one knew at the time for how long the crises would last (Chan,

2003). Schools set up web pages, mostly giving instructions on set reading and

uploading worksheets. After the outbreak was contained and schools reopened, it

was considered a priority that schools invest in IT infrastructure. The demand

for online teaching and learning was heightened in the 2009-2010 swine flu

outbreak and the World Health Organisation's resultant warnings about a

possible flu pandemic (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014) .

Having used

Blackboard as a student, and Blackbaud and Moodle as both a teacher and a

student, I have seen a range of approaches to VLEs or online learning (OL),

ranging from using the platform as a kind of digital filing cabinet, through to

a genuinely interactive space, with forums for students to discuss their ideas,

and choices in terms of content and structure of learning activities. However,

the world of technology, both online and offline, has had a dramatic impact on

what and how music students learn – YouTube alone

opens up a myriad of material that students would previously have been unable

to access away from school (Wise, Greenwood and Davis, 2011). This all leads to

a re-evaluation: it is not only a case of ‘putting what I use online’.

Project goals

As a result of

the VLE's context and my own previous personal experiences with online learning

platforms, my goals for this project and for Firefly were to:

• Establish the

type and style of learning experience that I was writing for

• Research ideas

on best practice for issues such as:

o Layout

o Readability

o Content and learning

design

o Current trends

in education technology

• Establish a

conceptual framework that takes the research into account, but also recognises

that every learning environment is unique in terms of student cohort

• Have a mix of

learning experiences that support both computer aided instruction (CAI) and

computer aided learning (CAL) (Southcott & Crawford, 2011)

•

Provide relevant unit

and assessment information

•

Populate the pages with

a range of learning resources

•

Specific learning

activities where appropriate.

• Use this

framework to make choices regarding the learning experiences being created.

As seen in via

screen shots, screen film and examples, not all of these goals were achieved.

What style of online learning does Firefly enable and support?

Getting started

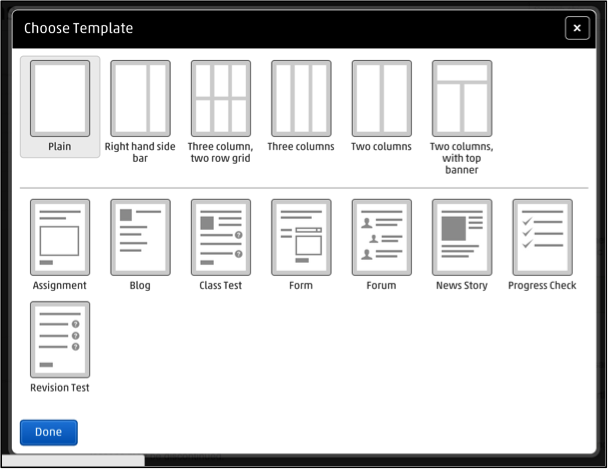

My faculty

explored Firefly at a faculty meeting on September 3. Under directions from

senior management, we discussed aspects of 'house style'. As we explored the

site, it became clear that certain choices relating to font, text colour, size

and formatting were limited. Font was pre-set and could not be altered; the

colour, size and layout headings and subtitles were restricted, and layout was

one or two columns, with no options to 'wrap' text. Embedded film or web pages

were pre-set to take the entire width of the working space. Images could not be

bordered simply by a thin black line, but needed to be framed by graphics of

picture frames or cards. Images were not collapsible. The system's main visual

interface was also predetermined and cannot be changed by individual users -

unlike a platform such as Moodle where Figure 1 each user can make choices about the

colour and style of the frame of their viewing. School

management decided on the main menu and subsequent drop down menus (see Figure

1). Individual staff can add only add pages to their own learning areas.

My faculty

explored Firefly at a faculty meeting on September 3. Under directions from

senior management, we discussed aspects of 'house style'. As we explored the

site, it became clear that certain choices relating to font, text colour, size

and formatting were limited. Font was pre-set and could not be altered; the

colour, size and layout headings and subtitles were restricted, and layout was

one or two columns, with no options to 'wrap' text. Embedded film or web pages

were pre-set to take the entire width of the working space. Images could not be

bordered simply by a thin black line, but needed to be framed by graphics of

picture frames or cards. Images were not collapsible. The system's main visual

interface was also predetermined and cannot be changed by individual users -

unlike a platform such as Moodle where Figure 1 each user can make choices about the

colour and style of the frame of their viewing. School

management decided on the main menu and subsequent drop down menus (see Figure

1). Individual staff can add only add pages to their own learning areas.Designing content - format and usability

Figure 2

I was

reluctant to add further clicks: however, not everything I need or want to

include can be included on a page without a lot of scrolling, which has also

been shown to be problematic (Nielsen, 2010). I have mitigated this problem

somewhat by using columns – however, in a choice between more

clicks and some scrolling, I have opted to keep a consistent menu of pages for

each unit. Each unit will have a general learning page with unit information,

resources and links, separate pages for specific lessons that require

audio/visual support, and a separate page for assessment information (See Figure 3).

I was

reluctant to add further clicks: however, not everything I need or want to

include can be included on a page without a lot of scrolling, which has also

been shown to be problematic (Nielsen, 2010). I have mitigated this problem

somewhat by using columns – however, in a choice between more

clicks and some scrolling, I have opted to keep a consistent menu of pages for

each unit. Each unit will have a general learning page with unit information,

resources and links, separate pages for specific lessons that require

audio/visual support, and a separate page for assessment information (See Figure 3).

As Firefly has

the capability for students to submit work online and for teachers to grade it

there, it may that a separate page for unit assessment will not only clarify

the structure and purpose for each page but also help students to find what

they need quickly. As each MYP unit needs to follow the same system of teaching

and assessment, this way my Firefly pages would mirror the 'routine' of the MYP

Arts framework, as well as helping to clarify the learning objective for each

page.

Figure 3

Online writing and design

Firefly

needs to accommodate the learning for students ages 11-18. Their online

learning and activity preferences are markedly different, as seen in Figure 4 below:

Figure 4: Age group differences (Nielsen, 2013)

To use an

example directly relevant to music teaching, my 11 year olds are likely to

appreciate animation and sound effects – however, when a key learning outcome is to focus on musical elements,

using sound effects may detract or distract from this objective. For my 14-15

year old students, their patience is much more limited for each of the above

columns/activities – in short, whatever I do is likely

to bore some of them. However, I can still follow Nielsen’s advice in other ways: mostly through minimising

text, writing at about a 6th grade level, and trying to provide

online learning experiences that are directly relevant, while still trying to

allow for space for students to look for extension or support material and to

support an inquiry learning model, and not just focus on ‘content delivery’.

PARC

Where

formatting allows, I have tried to adhere to the principles of PARC:

oProximity

oAlignment

oRepetition

oContrast.

Of these four,

alignment has been the easiest to implement. Repetition is something that

Firefly has a direct effect on, as they have limited the ways we can format

headings, and many of these involve colour, tied to different purposes (see

Figure 5).

We have limited options

on what font size or colour to use: apart from Arial 12 as the ‘normal’ text,

we only have these options. On one hand, this makes repetition easier – and the

font choice shows an awareness that dyslexic students find Arial easier to read

(British Dyslexia Association, n.d.).

Following instruction

from the school’s management, we were asked to use the colour headings “where

possible”, as students would find these more attractive. We were also asked to

use “lots of pictures and web links”. While on the surface this seems

reasonable, it does bring up some other usability and cognitive processing

issues.

Using graphics as visual support

One of the things I have had to grapple with is how to provide listening/musical

resources. Copyright concerns mean that my primary resource for posting audio media is YouTube. Given

that embedding a Figure 5: YouTube links means having a lot of visual media on the page,

I made the decision not to use further graphics unless they were needed to

directly illustrate a musical point – such as showing an example of a musical

scale, an instrument, or a section of a score. This decision also supports the

findings and recommendations of Jakob Nielsen on graphics, which advise that

graphics should show ‘real content’ rather than just be decorative (Nielsen,

2001). Henderson (2006), points out that decorative images takes up

cognitive/processing time while the reader works out if the graphic is relevant.

Henderson notes that images that simply reinforce the meaning of the text play

differently to different audiences:

……young students, poor readers, and readers

with low domain knowledge benefit from redundant images. They move back and

forth to make meaning of the text. Unfortunately redundant images slow down students

with effective literacy skills and high content knowledge. (Henderson, 2006).

Southbank does not actively accept students with identified special

learning needs; however we do have a small proportion of students who are

dyslexic, have ADHD, dysgraphia or other issues, such as those identified as

being academically gifted. We are an

international school with a 20-30% student turnover each year, and we support a

(proportionally) large number of EAL students. We also offer strong support for

mother-tongue students, as well as mandatory second language teaching, in line

with the global citizen philosophy of the IB. For these students, semantic

chunking is hugely important - the use of graphics can either support or

disrupt their learning process. What may slow down one kind of reader may

support another, and this will be a constant challenge. For example, I

originally used this picture to show what a banjo is (Figure 6): while this

picture presents a banjo in a relevant context, if the main point is to illustrate

the instrument, then the photo in Figure 7 may be more appropriate.

Figure 7: Banjo

http://pixabay.com/en/banjo-musical-instrument-strings-31562/

Where the page’s main focus is a ‘hook’ to engagement or

interest, pages can offer a wider range of graphics. For example, the faculty’s cover pages need to stimulate

further interest rather than being tied to a specific learning objective (Figure 8).

Scanability

Henderson also discusses

‘scannability’ – this deals with how easy it is for students to understand what

kinds of information are on the page, and includes ideas like writing

concisely, starting with the main point, using bullet points, and highlighting

or bolding keywords. These are ideas I have tried to Figure 8 utilise: however, to work to the inquiry cycle of the MYP, starting with the

main point can be counter-productive in that sometimes the learning objective

can be focused on the learning skills needed for discovery rather than mastery

of a particular topic: I find the ‘top-down’ approach more useful when I do a lesson

that is mastery based. This conflict is something I will need to examine

further more and more learning activities are placed online.

Cognitive loading

Cognitive

loading refers to the idea that humans have a limited amount of processing

power accessible to them at any one time. Whitenton (2013) advocates three

basic principles to minimize ‘extraneous cognitive load’ where processing power is required even when the

processing is not contributing towards understanding. The principles are:

· Avoid visual

clutter (this is discussed above in terms of graphics)

· Use labels and

layouts that are common to other online sites

· Offload tasks

that require readers to make decisions or remember information that is not key

to the objective.

Of these three

it is the last that has presented me with some doubt: offloading that which is

not essential runs the risk of reductionism if taken to the extreme. For this

school, for this approach to learning, I believe that there are times when this

will be useful, but also times when having extra information, extra links, may

just inspire a creative thought. I did think about having a separate ‘resources’ page but if

teenagers and other readers don’t even want to scroll, asking them

to jump all over Firefly might mean they don’t bother.

Other scanability issues

·

White space: Henderson advocates

leaving white space between paragraphs and sections: unfortunately, Firelfy

auto-edits white space. For example, if I want to leave a couple of lines

‘white’ between paragraphs, once I click the ‘Done’ button, Firefly will delete

the extra lines.

·

Justification: Working in two columns

to minimise scrolling has demonstrated Henderson’s point that uneven starts to

lines is harder to process. I have kept lineation to the left margin.

Allowing for asynchronous development

One of the benefits of an online

learning environment is that activities can be structured in a way that allows

much more room for asynchronous development. A huge range of support materials

and activities can be offered in a way that allows students to take activities

and process information in their own time (Palloff and Pratt, 2001).

Opportunities for asynchronicity also allow for students to participate in a

more meaningful way: when time is not a factor, participation may be more

likely to be genuine (Palloff and Pratt, 2005), leading to opportunities for

collaboration.

Wikis offer the

opportunity for genuinely collaborative construction of knowledge and have been

seen to have a positive effect on students’ engagement in learning (Chou and Chen, 2008; Dimitrious

and Jimoyiannis, 2013). While Firefly can host a forum (see Figure 9), it

does not have the capability to host a wiki. It is possible to host a range of other media, including Google docs (see Figure 10), but staff do not have school based Google drive accounts. As internet and online safeguarding is a key priority at the school, staff are not permitted to communicate with students using private Google/gmail addresses. For the moment, not having school Google email means that students can create documents collaboratively but cannot share with staff as anything other than (perhaps) a PDF of a draft or final document. Staff cannot see who contributed what, and therefore have limited capacity to monitor or guide the Figure 9 use of this very effective learning tool and teach students how to construct knowledge in a truly collaborative way. I would also like to be able to use wikis, as they can provide opportunities and support for collaboration by making the “quantity and quality of each group member's contribution more transparent, potentially encouraging participation and making it easier to mark group work” (Elgort, Smith & Toland, 2008, p. 197). Wikis and other collaborative Google docs may help to support truly group based, online learning activities (Feng & Beaumont, 2010).

Palloff and Pratt (2005) note that

students new to online learning activities need to be taught how to behave in

the online learning environment, just as they would in the physical classroom.

The teaching approach should involve defining time expectations, explicit

instruction on ways to build a sense of community (such as logging on often and

contributing to online discussions in a respectful yet critical way), and by

being prepared to step in to redirect or encourage when needed. This is not

simply a case of teaching students how to use specific pieces of software, or

how to evaluate online sources (Palloff and Pratt, 2000), even though these are

both important learning skills. There is a need for this kind of explicit instruction

and facilitation, no matter the technical platform of the learning space

(Hai-Jew, 2008).

The screencast below travels through a Grade 6 unit, including a forum, which has explicit instruction on behaviour:

Figure 10

These pages offer a range of learning activities, links to resources, audio files and assessment information. As this is Southbank’s first foray into an online learning platform, and the information on requirements has been inconsistent, it may take some time to develop a scaffold a consistent, while-school approach. The underlying approach should be based on a constructivist philosophy that values the social and collaborative construction of knowledge and places this as fundamental to the learning process. What might be useful is a school wide statement on how they expect students to use the VLE: expectations, restrictions, and guidelines. At the moment, the school plan is that when Firefly is launched to students, they will receive specific training, focusing not only on the mechanics of entering and using the space, but also educating them on the kinds of choices they should be making in regards to online learning, participation and behavior (van Loon, Ros & Martens, 2012).

Palloff and Pratt (2001) argue that “Unlike the face to face classrooms, in

online distance education attention needs to be paid to developing a sense of

community in the group of participants in order for the learning process to be

successful” (p. 20). There is an assumption here -

either that online communities need extra support when the face-to-face

interaction is lacking, or that this sense of community is not so important

when everyone is on the same place at the same time. While Southbank is not a

distance leaning context, creating rich problem solving experiences for groups

is an important part of the MYP program, and the online learning that we design

needs to support this.

Learning how to use technology

While

preparing material and posting it to Firefly, I have learned how to:

- Build and host a Prezi

- Create an embed code for a web page

- Create a screencast (using Quick Time on a Macbook)

- Wrap text in Microsoft Word

- Create a YouTube channel and playlist

- Set up a SoundCloud page

Southbank has

quite strict rules on using social media, and this has mean that using

technology such as Twitter or Facebook is out of the question, despite recent

research that examines how such platforms can provide positive opportunities

for students to develop stronger bonds between their school-based and

out-of-school learning and experiences (Nowell, 2014).

Soon.....but not yet!

Using online music technology can open up a classroom to popular music sounds, while still using traditional music theory as a springboard for composition and performance (Cain, 2004). The next

steps I foresee in integrating other kinds of education technology with/into

Firefly are:

- Learning how to add audio to my screencasts (without having to pay for it!). This could be useful for notation learning, or for teaching how to use music technology

- Filming demonstrations – for using instruments, setting up MIDI or sound recording equipment, demonstrations of annotating musical scores

- Instructional animation – also useful for demonstrating annotation

- Developing ways to create links between Firefly and online music technology: while software such as Garageband, Logic and Finale need to be hosted separately, I have started looking at ways to build activities that are based on using free, internet-based programs, such as Hook-Pad (Hook Pad, 2014), beatlab (beatlab, 2014) and music squares (Wu, 2011). One example of this from can be seen in the screenshot below (Figure 11):

s

Figure 11

I

Having explored Minecraft, I can see it’s usefulness for other learning

disciplines such as humanities, English and PSHE (Personal, Social and Health

Education), but it’s lesser relevance to the current MYP and DP music programs mean that it

is not a priority. One study on the use of games in the music classroom reports increased motivation to use multimedia, but does not demonstrate an equal increase in the quality of learning objectives or student achievement (Gomes, Figueiredo, & Bidarra, 2013). I have embeded game based learning activities in Firefly pages for objectives such as learning the rhythmic values of notes: one game in particular has proved very popular (Garrett, 2013), and I would hope in future to develop my own video/online games that work in similar ways for other learning objectives. I am currently working on a game that helps students to learn the notes of the musical staff, and through playing the game they build their own melody.

McGloughlin

(2007) examines e-learning as a space that can “provide a raft of e-learning experiences, improved

access, and democratization” (223), while acknowledging that there are many

challenged, such as being able to accommodate both global and local

perspectives, a blend of generalization and differentiation, and being able to

provide stability/uniformity while still accommodating diversity. There is also

research that examines the potential of online learning to actually “reduce

cultural misunderstanding and build mutual respect and trust to improve the

quality of education” in a global context (Liu, 2007, p. 36). These are all

challenges that I feel I have yet to fully engage with in the construction of

the music learning spaces on Firefly.

Assessment

via Firefly is not something I will tackle until students are comfortable

finding their way around the site. The system does have the capacity to return

work with critical commentary: I have used this (via Moodle) in the past and

found that students appreciate having their feedback all in one place. Another benefit is that feedback on tests and quizzes can be almost immediate, depending on the test design. However,

the MYP requires the use of an arts process journal, which may be print or digital. This may mean that

students still need to print and/or store this information elsewhere for the

purposes of external moderation. Linking to an online portfolio system through Google docs or Mahara (Mahara, 2014) may be useful as a next step in developing the arts journals and giving students a more substantial way to display their work over a number of years.

Conclusion

Even after

the research, a huge amount of time learning how to use the interface, and

setting up several units and pages, I do not consider these pages ‘complete’. To begin

with, many of these learning activities are either new or fully revised to meet

the demands of the new MYP curriculum framework, or the Diploma Program course

that I am teaching for the first time. Part of setting up this kind of learning

environment is that it is iterative – the space

will never be static. The learning needs of each cohort will be different, and

I will also continue to develop and extend not only my education technology

skills, but also my general teaching skills in designing learning activities

that engage students.

My main aim

has been to provide a learning space where students find something that extends

their understanding and tweaks their curiosity. At this point, the most

successful pages still tend to be those that focus on a specific learning

objective – for example, the Grade 8 page on the contexts of

the Blues, an the Grade 6 page on learning the notes of the musical staff. The

least successful are those where I have tried to provide a range of options for

learning – part of this is about letting go some control and valuing the individual

learning process of students. This is probably what I have learned the most from this

project – that I cannot control every learning experience of the students, and

that stepping away from this control note only gives them more freedom to learn

in the way that best suits them, but also offers them more opportunities for

extension, discovery and inquiry, which are all keys to lifelong learning. By enabling me to offer students a wider variety of choices in how they learn, I hope that Firefly will serve to raise engagement and enjoyment of music.